Immune Thrombocytopaenia (ITP)

Disclaimer

These guidelines have been produced to guide clinical decision making for the medical, nursing and allied health staff of Perth Children’s Hospital. They are not strict protocols, and they do not replace the judgement of a senior clinician. Clinical common-sense should be applied at all times. These clinical guidelines should never be relied on as a substitute for proper assessment with respect to the particular circumstances of each case and the needs of each patient. Clinicians should also consider the local skill level available and their local area policies before following any guideline.

Read the full PCH Emergency Department disclaimer.

|

Aim

To guide PCH medical staff with the assessment and management of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

Definition1-3

ITP is an uncommon disorder, affecting 1- 3 in every 10,000 children. The platelet count is < 100 x 10

9/L, and may be as low as < 20 x 10

9/L. Children present with petechiae, purpura (bruising), and sometimes mucosal bleeding. Rarely there may be rectal bleeding or haematuria. The risk of intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) is < 1%.

Background1-5

- ITP is the most common cause of thrombocytopenia in childhood.

- It is the result of immune mediated destruction of platelets, often precipitated by viral infections, and there are no other coagulation problems.

- Children present between the ages of 2 - 10 years, with peak incidence in the preschool years.

- ITP can be divided into two clinical syndromes:

- Acute ITP - 90% of children. These patients present acutely with spontaneous bruising, and the ITP resolves within weeks to months of diagnosis.

- Chronic ITP - 10% of children. This lasts more than 6 months, and often beyond 12 months. The presentation may be more insidious.

Assessment

- Well children presenting with petechiae and purpura; mucosal bleeding is uncommon.

- The clinical assessment is aimed at excluding other causes of petechiae / purpura and thrombocytopenia e.g. malignancies.

- The severity of the disease is determined by the clinical picture, not the platelet count, which may be < 20 x 109/L

- Intracerebral haemorrhage is rare, but should be considered in any patient with ITP presenting with neurological symptoms or signs.

Consider increased risk factors for intracranial haemorrhage (ICH)

- head trauma

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDS) in last 5 days

- haematuria – micro or macroscopic

- history of prolonged/episodic mucosal bleeding

- bleeding from multiple mucosal sites.

|

History

- Petechiae and purpura – type, severity, duration.

- Mucosal bleeding - epistaxis, haematuria, rectal bleeding, severity and duration.

- Previous haemostasis problems with procedures.

- Systemic symptoms - especially any recent viral infections in the last 6 weeks.

- ICH should be considered if there are CNS symptoms or signs such as lethargy, headache, vomiting, reduced level of consciousness.

- Possible systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) - photosensitive rash, arthritis, myalgia, oral ulcers, hair loss, dry eyes or mouth, fatigue, weight loss, fever. Consider in older children, high risk ethnic background (e.g. Aboriginal, Asian, African, Maori).

- Possible malignancy: chronic pain, fevers, weight loss, pallor.

- Recurrent infections: suggestive of immunodeficiency.

- Recent live virus vaccination (e.g. MMR).

- Medications: quinine, penicillin, digoxin, anti-epileptics, salicylates, heparin, warfarin.

- Family history: SLE, thrombocytopenia or other haematological or immunological disorders.

- Co-morbid conditions that may increase the risk of bleeding.

- Lifestyle factors that may pose a risk for trauma and bleeding.

Examination

- Usually a well looking child with normal observations

- Bleeding signs: document location and size of purpura, areas of petechiae. Look for mucosal bleeding, check for retinal haemorrhages.

- There should be NO pallor, lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. These findings are NOT consistent with ITP

- No evidence of infection

- Full, documented CNS examination

- Dysmorphic features: suggestive of a congenital syndrome e.g. Fanconi Syndrome, Thrombocytopenic-Absent Radius (TAR) syndrome.

Investigations

- Urinalysis for haematuria at every presentation:

- Tranexamic acid is contraindicated in haematuria

- Haematuria is associated with an increased risk of ICH.

- Full Blood Picture (FBP): shows thrombocytopenia (may be < 20 x 109/L), normal haemoglobin, normal white cell count

- The blood film must be reviewed by a Laboratory Haematologist to confirm the film features are in keeping with the clinical diagnosis of ITP.

- Urgent cerebral imaging should be considered in patients with CNS symptoms and signs

- INR, APTT or clotting tests are not required unless significant haemorrhage or non-accidental injury (NAI) is suspected

- A bone marrow aspirate is rarely required, and is only considered when the diagnosis is uncertain and a haematological malignancy needs to be excluded.

Differential diagnoses

A broad differential diagnosis should be considered, especially for older children.

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (e.g. SLE).

- Haematological malignancies (e.g. leukaemia).

- Aplastic anaemia.

- Infections - viruses, meningococcal disease.

- Drug induced thrombocytopenia.

- Haemolytic uraemic syndrome.

- Other coagulation disorders e.g. disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

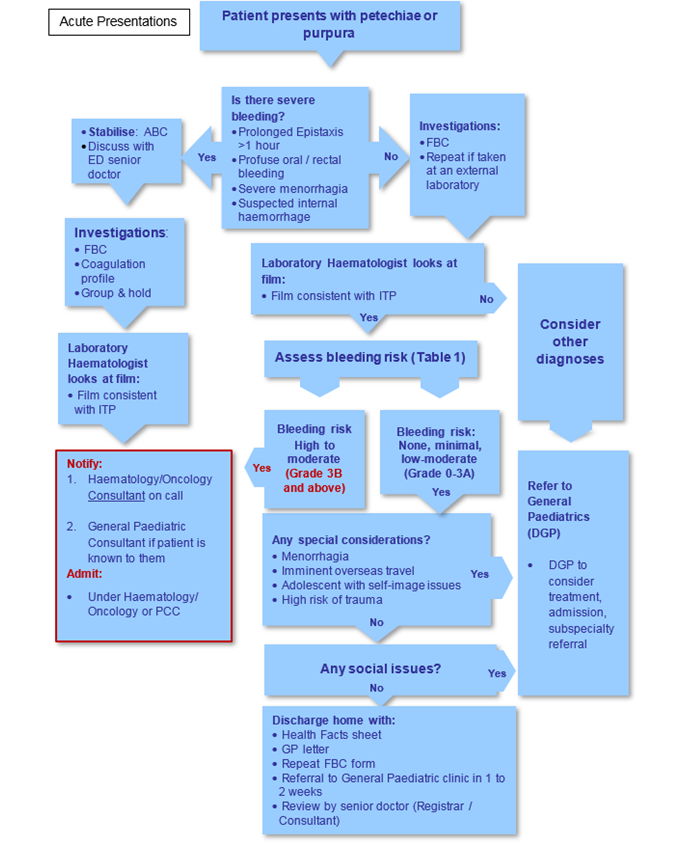

Management

- ITP will spontaneously remit without any treatment within 6 months in most paediatric patients.

- Treatment decisions should be based on bleeding rather than platelet count.

- The table below has been used in trials of paediatric patients with ITP to guide therapy decisions.

Table 1: Severity scoring of bleeding in patients with IPT4,5

| 0 |

None |

No new haemorrhage of any kind

|

No treatment usually required |

| 1 |

Minor |

Few petechiae (≤ 100 total) and / or ≤5 small bruises (≤3cm diameter), no mucosal bleeding

|

No treatment usually required

|

| 2 |

Mild |

Many petechiae (>100 total) and / or large bruises (>3cm diameter)

|

No treatment usually required

|

| 3A |

Low risk moderate |

Blood crusting in nares, painless oral purpura, oral/palatal petechiae, buccal purpura along molars only, mild epistaxis ≤5 min

|

No treatment usually required

|

| 3B |

High risk moderate |

Epistaxis > 5min, haematuria, haematochezia, painful oral purpura, significant menorrhagia

|

Treatment usually indicated |

| 4 |

Severe |

Mucosal bleeding or suspected internal haemorrhage (brain, lung, muscle, joint etc.) that requires immediate medical attention or intervention

|

Treatment usually indicated

|

| 5 |

Life threatening/fatal |

Documented intracranial haemorrhage or life-threatening or fatal haemorrhage at any site

|

Treatment usually indicated

|

Management of patients with no to low / moderate risk of severe bleeding (Grade 0 to 3A)

These patients:

- Have skin manifestations of ITP, or a history of mucosal bleeding which has stopped at the time of clinical assessment and was not prolonged (see Table 1).

- Can usually be managed conservatively without treatment, with outpatient follow-up.

- May be considered for treatment in exceptional circumstances such as imminent overseas travel, adolescent with self-image issues, or a high risk of trauma.

Management of patients with special considerations/social issues

- These patients:

- Have menorrhagia, imminent overseas travel, self-image issues, high risk of trauma, social issues

- May need treatment with steroids and/or admission under General Paediatrics.

Management of patients with increased risk of ICH

Patients with:

- haematuria, history of prolonged/episodic mucosal bleed and/or bleeding from multiple sites should be considered and managed as per Grade 3B high-moderate risk

- head trauma, NSAIDS in previous 5 days may need treatment with steroids and/or admission under General Paediatrics.

Management of patients with high-moderate risk (Grade 3B)

These patients:

- have epistaxis >5mins, haematuria, rectal bleeding, painful oral purpura, or significant menorrhagia

- usually require treatment

- Should be admitted under the haematology/oncology team.

Notify the general paediatric consultant if the patient is known to them.

Treatment for high-moderate risk

- Does not influence the natural history of ITP, but can acutely raise the platelet count

- Should be discussed with the haematology/oncology Consultant on call

Table 2

| 1. Total duration of epistaxis >5 and <20 minutes |

Admit for observations

- + steroid

- +/- tranexamic acid

|

| 2. Total duration of epistaxis > 20 minutes < 60 minutes |

- Admit for steroids

- +/- IVIG

|

| 3. Total duration > 60 minutes |

- Treat as severe bleed with steroids and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg)

|

| 4. Epistaxis of any duration with multiple sites of mucosal bleeding |

- Treat as severe bleed

- Assess for increased risk of intracranial haemorrhage

- Treat with steroids and IVIg

|

Table 3

| 1. Prednisolone |

4mg/kg/day orally (max 200mg) in 2-4 divided doses for 4 days 4,7 |

- Consider as first-line treatment

- Oral prednisolone is available in 1mg, 5mg and 25mg tablets as well as a 5mg/mL liquid.

|

| 2. IVIg |

See doses below. |

- All requests for IVIg should be directed to the National Blood Authority (NBA – Bloodstar).

- Requests that do not meet the NBA criteria require an Individual Patient Application (IPA) to the CAHS Drug & Therapeutics Committee (DTC).

|

| 3. Tranexamic Acid |

25mg/kg orally (up to 1.5 g maximum), three times daily for 3 to 5 days with medical review at day 5.4,6 |

Consider as adjunct to steroids and IVIg (contraindicated in haematuria):

- Oral tranexamic acid is available in 500mg tablets. Tablets are scored and can be cut in half.

- For doses not in increments of 250mg, an aliquot can be performed by dispersing the tablets in 10-20mL of water and administering a portion of the resulting liquid.

- If the tablets are unavailable, tranexamic acid injection can be diluted with water and given orally.

|

Management of severe bleeding

- Severe bleeding needing immediate intervention includes:

- Epistaxis for more than 1 hour

- Profuse oral or rectal bleeding

- Severe menorrhagia

- Any internal haemorrhage (including intracranial haemorrhage)

- Discuss the management of these patients immediately with the on call General Paediatric Consultant and Paediatric Clinical Haematologist (and the General Surgical Team, Neurosurgical Team, ENT Surgical Team if required).

- Manage Airway, Breathing, Circulation

- Establish IV access (large bore cannula if possible)

- Obtain urgent Group and Hold +/- cross matched cells

- Consider blood transfusion to achieve homeostasis

- Seek surgical assistance to manage bleeding.

Treatment for severe bleeding

- Platelet transfusions: should only be given for intra-cranial haemorrhage or other life-threatening bleeding

- Contact Transfusion Medicine laboratory and request emergency platelets

- Methyprednisolone: a dose of high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (15-30mg/kg/day, up to 1g maximum) may be given for intracranial haemorrhage whilst waiting for the platelets to arrive.

- In the presence of severe bleeding causing clinical instability: consider intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) 0.8g / kg as a single dose as it can raise the platelet count rapidly.8

- Consider tranexamic acid 10 mg/kg (up to1g maximum) intravenously as a single dose. 4,6

- Frequency to be advised by a paediatric haematologist.

- Refer also to the methylprednisolone monograph (WA Health only) autoimmune / inflammatory disorders section for guidance.4,9

|

Admission criteria

Bleeding Grade 3B and above:

- Notify haematologist/oncologist on call and admit under the haematology/oncology team.

- Notify general paediatric consultant if the patient is known to them.

- Bleeding Grade 0 to 3A with unclear diagnosis/special considerations/social issues/head trauma/NSAIDS use – discuss with paediatric consultant on-call.

- If unsure after hours, discuss with the on-call Emergency Consultant; consider admission to the ED Short Stay Unit.

Discharge criteria

Patients can be sent home from the Emergency Department when:

- The diagnosis is definite and there is no active bleeding.

- The child is well and the social situation is such that there is good parental supervision and safety in the home (with respect to the risk of trauma).

- There is the opportunity to reassure and educate the parents in the Emergency Department.

- There is appropriate follow up arranged with the general paediatric team within the next 1-2 weeks.

Referrals and follow-up

- Patients discharged with ITP require review by a senior doctor (Registrar or Consultant) to reassure parents and discuss outpatient management. If discharged from ED by a Registrar this should be discussed with the Consultant General Paediatrician on-call.

- Refer to General Paediatrics Outpatients.

- Referral to the Paediatric Haematology Outpatient clinic can be done by the general paediatric team if the diagnosis remains uncertain, the white cell count is abnormal, the blood film is atypical, there is failure to respond to treatment or platelets have not resolved in 6 months (Chronic ITP).

- Rheumatology referral if history or examination suggestive of SLE.

- The platelet count should be monitored no more frequently than weekly.

Additional considerations:

- Avoid IM immunisations until resolution, although in chronic cases this may need to be on a risk-benefit assessment.

- Stop / do not prescribe non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

- Avoid contact sports until resolution.

Rural patients

- Discuss the diagnosis and management with the nearest local Paediatrician.

- If unavailable, discuss with the on-call general paediatrician at PCH.

- Bleeding Grades 0 to 3A can be managed locally, without the need to transfer to PCH.

- Bleeding grade 3B may be managed locally but should be discussed with the on-call Haematologist / Oncologist.

- Bleeding Grades 4 and 5 will need to be transferred after stabilisation

- See the 'Useful Resources' section for the GP letter and Health Fact Sheet for parents.

Health information (for carers)

- The patient should avoid trauma – specifically no bicycles or trampolines.

- The patient should not take any non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications e.g. ibuprofen.

- Provide ITP Health Fact Sheet.

Documentation and Communication

- Provide referral to the General Paediatric Team Outpatient Clinic.

- Print ITP GP Letter and fax / post to the GP.

- Give the ITP Health Fact Sheet to the family.

- A FBP request form should be given to the family to arrange prior to their outpatient appointment (should be done within 2 weeks of the appointment).

References

- Cole C. Rapid update on childhood immune thrombocytopenic purpure. J Paediatrics & Child Health. 2012;48 pp378-9

- Provan D SR, Newland A C, et al. International consensus report on the investigation and management of primary immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2010;115(2) pp168-86

- Schoettler ML, Graham D, Tao W, Stack M, Shu E, Kerr L, et al. Increasing observation rates in low-risk pediatric immune thrombocytopenia using a standardized clinical assessment and management plan (SCAMP(R)). Pediatric blood & cancer. 2017;64(5).

- Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service. Newly Diagnosed Immune Thrombocytopenia (ND-ITP) in Children. Clinical Guideline. June 2019.

- Grainger J D. Suspected or known Immune Thrombocytopenia Management Plan (Children). Central Manchester University Hospitals, NHS Foundation Trust. 2015. http://www.uk-itp.org/docs/ITP/suspected_or_known_immune_thrombocytopenia_management_plan__children_.pdf

- Australian Medicines Handbook, Children’s Dosing Companion. Tranexamic Acid. Last updated July 2019.

- Cooper N. A review of the management of childhood immune thrombocytopenia: how can we provide an evidence-based approach? British Journal of Haematology. 2014;165(6):756-67.

- Neunert C, Lim W, Crowther M, Cohen A, Solberg L, Jr., Crowther MA. The American Society of Hematology 2011 evidence-based practice guideline for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2011;117(16):4190-207

- Beck CE, Nathan PC, Parkin PC, Blanchette VS, Macarthur C. Corticosteroids versus intravenous immune globulin for the treatment of acute immune thrombocytopenic purpura in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Pediatr. 2005 Oct;147(4):521-7. PubMed PMID: 16227040. Epub 2005/10/18. Eng.

| Endorsed by: |

Director, Emergency Department and Department of General Paediatrics |

Date: |

Jun 2020 |

This document can be made available in alternative formats on request for a person with a disability.