Fractures - Overview

Disclaimer

These guidelines have been produced to guide clinical decision making for the medical, nursing and allied health staff of Perth Children’s Hospital. They are not strict protocols, and they do not replace the judgement of a senior clinician. Clinical common-sense should be applied at all times. These clinical guidelines should never be relied on as a substitute for proper assessment with respect to the particular circumstances of each case and the needs of each patient. Clinicians should also consider the local skill level available and their local area policies before following any guideline.

Read the full CAHS clinical disclaimer

|

Aim

This guideline provides PCH Emergency Department (ED) staff with an overview of how to assess and manage limb fractures in children. There are specific guidelines for each fracture – please refer to these for specific management.

Background

- Fractures in children are more likely than sprains and ligamentous injury due to relatively lower bony strength.

- Anatomical and physiological differences between adults and children account for the unique fracture types seen in paediatrics such as torus (buckle), greenstick, bowing, physeal (Salter Harris) and avulsion fractures.

Describing fractures

1. Skin integrity

- Closed: Overlying skin is intact.

- Open (compound): Damage to overlying skin and soft tissue results in exposure of the bone.

2. The type of fracture (relates to the mechanism of injury):

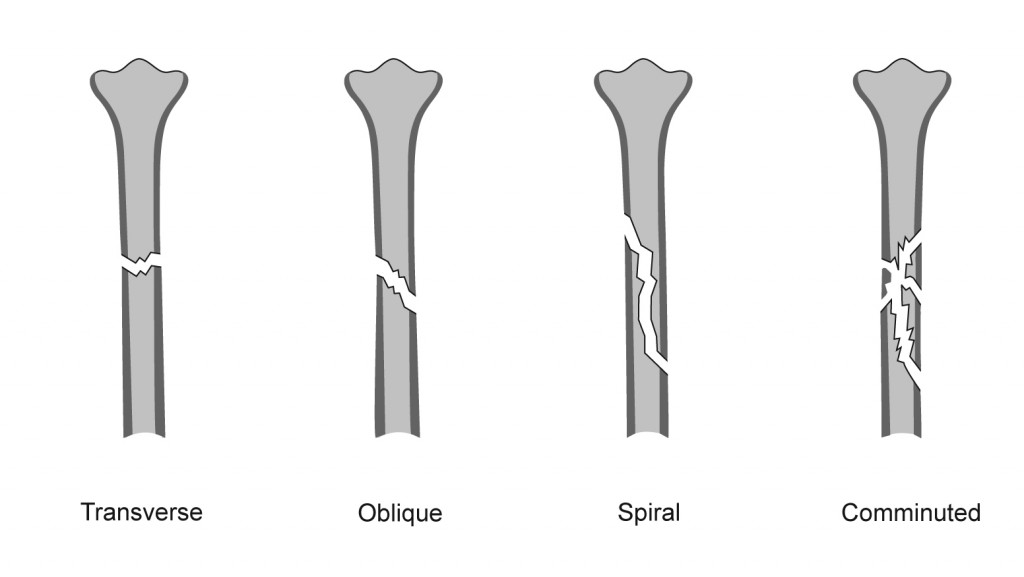

- Complete fractures:

- Transverse

- Oblique

- Spiral

- Comminuted – several fracture lines resulting in at least three fragments

- Incomplete fractures unique to children:

a. Plastic deformity b. Buckle fracture c. Greenstick fracture

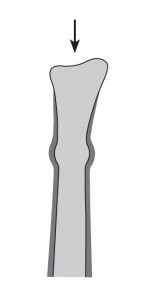

| Buckle (torus) fracture |

Usually occurs at the metaphysis and is the result of relatively mild compression / impaction forces along the long axis of the bone. The periosteum remains intact and is a relatively stable fracture. |

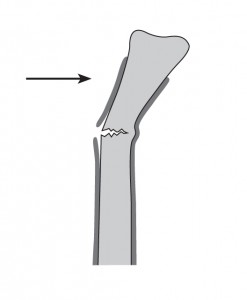

| Greenstick fractures |

Usually occurs at the metaphysis and is the result of relatively mild compression / impaction forces along the long axis of the bone. The periosteum remains intact and is a relatively stable fracture. |

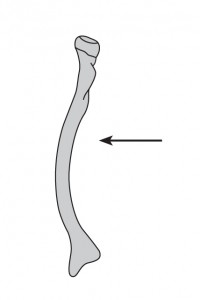

| Plastic deformity (bowing) |

Results from stress beyond the bone's capacity for recoil. The periosteum and bone cortices remain intact. Seen most frequently in the fibula and ulna and typically with fracture of the paired long bone. |

3. Relationship of the bone ends relative to each other

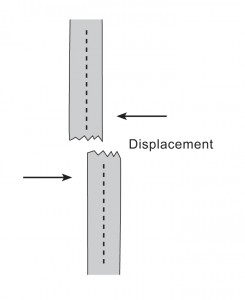

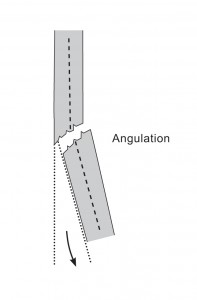

| Displacement |

The percentage of the bones diameter (at the level of the fracture) by which one fragment is displaced from or overrides the other. |

| Angulation |

Angulation of the distal fragment relative to the proximal fragment. |

| Rotation |

Rotation (in the axial plane) of the distal fragment relative to the proximal. |

| Shortening |

Complete fractures are unstable, and muscle traction forces may result in the distal fragment being pulled proximally resulting in a relative shortening of the bone. |

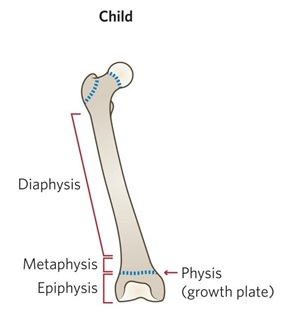

4. Part of the bone involved

- Diaphysis

- Metaphysis

- Growth plate (physis) - unique to children. Consult the Salter-Harris classification below.

- Epiphysis.

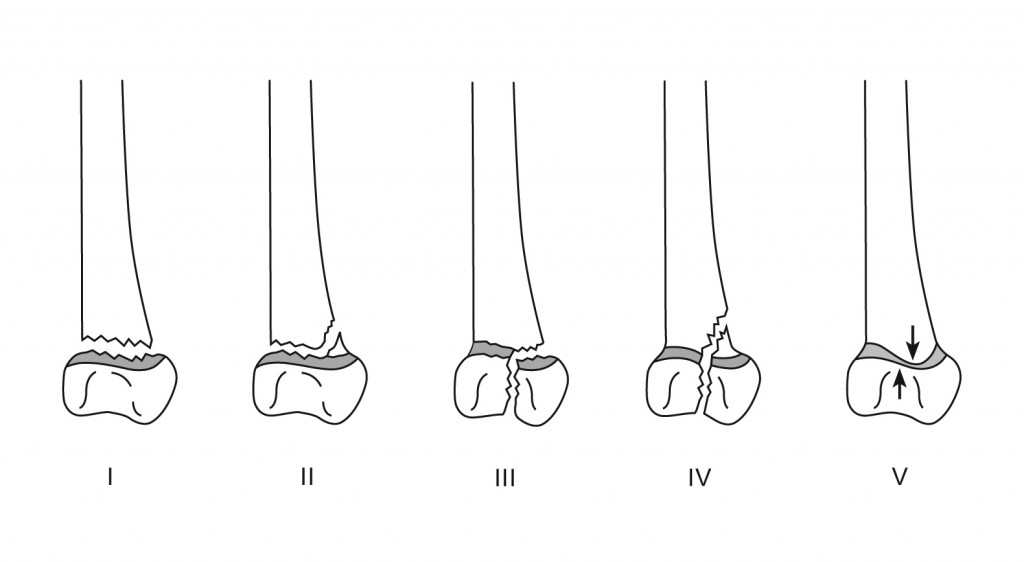

Salter-Harris classification

Any fracture that involves a growth plate must be referred to the Orthopaedic Surgical team.

- Salter-Harris I and II fractures – refer within one week.

- Salter-Harris III, IV, and V fractures – immediate referral.

| Salter-Harris I |

Growth plate separation within the physis. No damage to the metaphysis or epiphysis. |

| Salter-Harris II |

Fracture line across the growth plate with a component of the metaphysis attached to the displaced epiphysis fragment. |

| Salter-Harris III |

Fracture line enters the epiphysis from the physis. Commonly involves the articular surface with separation of the epiphysis fragment. |

| Salter-Harris IV |

Fracture line extends across the growth plate from the articular surface into the metaphysis. |

| Salter-Harris V |

Compression of part or all (rarely) of the growth plate. Very rare. Initial X-rays appear normal. |

5. Neurovascular status

- Assess motor function, sensation, pulses, and capillary refill time in the affected limb compared with the unaffected side.

- This is especially important for displaced fractures, supracondylar fractures of the humerus, knee fractures, and where compartment syndrome is suspected.

Assessment

- Suspect a fracture if there is pain, swelling or deformity.

- All injury presentations in children under 2 years must have an Early Childhood Injury Proforma completed (MR301.3)

History

- Document a clear mechanism of injury. The mechanism will provide an idea of the type of fracture expected.

- Neonates and young infants may present with irritability and / or distress without a clear history of trauma.

- Be aware of pathological fractures after minor trauma for children with conditions such as osteogenesis imperfecta, renal osteodystrophy, spina bifida, or bone tumours.

- Stress fractures may occur in adolescents after several weeks of vigorous sport.

Examination

- Major trauma patients should be assessed as per Major Trauma Management Pathway. See also Trauma - Serious injury guideline.

- Look for bruising, swelling, tenderness and deformity. Self-immobilisation of the limb may be evident.

- Assess neurovascular status – check distal pulses and perfusion, sensory and motor function.

- Look for puncture wounds and lacerations (open fracture).

- Assess the joints above and below the injury including passive and active movements.

Investigations

- Plain film X-ray is first line imaging for suspected fractures.

General management

- Analgesia

- Assess neurovascular status – if there is compromise, an urgent reduction may be required. Consult ED senior doctor or Orthopaedics urgently

- Immobilise the limb

- Assess skin integrity for open fractures (see management below).

- For specific fracture management, see Fractures – Quick Reference Guide

- Complete an Early Childhood Injury Proforma (MR301.3) for children under 2 years

Open Fractures

- Urgent treatment is needed to prevent infection

- IV antibiotics should be given without delay, refer to Bone and Joint infections

- Tetanus booster should be considered, refer to Tetanus prone wounds

- The open wound should be washed out in ED with sterile sodium chloride 0.9%

- Cover the wound with povidone iodine 10% soaked gauze

- Apply a backslab

- Notify Orthopaedic team early.

Non-Accidental Injury (NAI)

Consider NAI in the following cases:

- Delay between the injury and seeking medical advice for which there is no satisfactory explanation

- Inadequate supervision

- Repeated injuries

- Injury unexplained or unwitnessed

- Injury not consistent with the history

- Injury not consistent with the observed developmental stage

- Evidence of neglect

- Unusual behaviour

- Concerns regarding the carer

- Any fracture in a child not walking

- Multiple fractures

- Femoral shaft fracture < 2 years

- Spiral fractures of the humerus

- Corner or bucket handle (metaphyseal) fractures in infants.

ALL suspected NAI cases should be discussed with the ED senior doctor and / or Child Protection Unit (CPU).

References

- McRae R, Max Esser M, Practical Fracture Treatment Fifth Edition, Churchill Livingstone, 2008

- Rang M, Pring ME, Wenger DR. Kluwer W, Rang's Children's Fractures Fourth edition. Wolters Kluwer, 2018

| Endorsed by: |

Co-director, Surgical Services |

Date: |

Feb 2024 |

This document can be made available in alternative formats on request for a person with a disability.